Paper and History

One of the basic human needs, since prehistoric times, has been to capture images, words, thoughts and to share them without limitations of time or space. We have an idea of the world in prehistoric times thanks to the petroglyphs the cavemen used to record their lifestyle on cave walls. This was only the beginning. Slowly, stylized signs representing concepts or objects (hieroglyphs and ideograms) began to spread. Later came phonetic signs that represented the sounds of words. In this way the alphabet and writing were developed, as we know them today.

But on what material could be used to depict drawings, hieroglyphics and writing?

The first solution was found by the Chaldeans of Mesopotamia, currently Iraq. They fabricated clay tablets and engraved wedge-shaped signs on them while they were still soft. Once cooked, the written tablets would remain unchanged in the course of time.

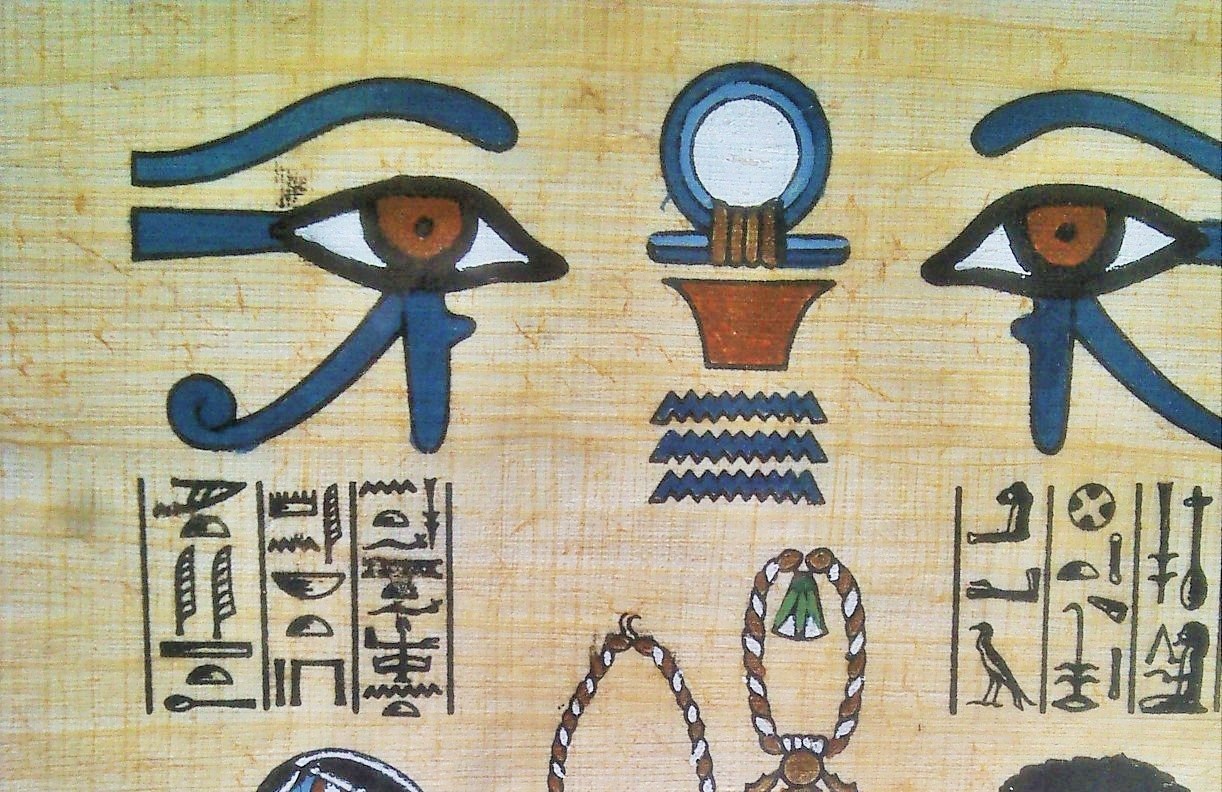

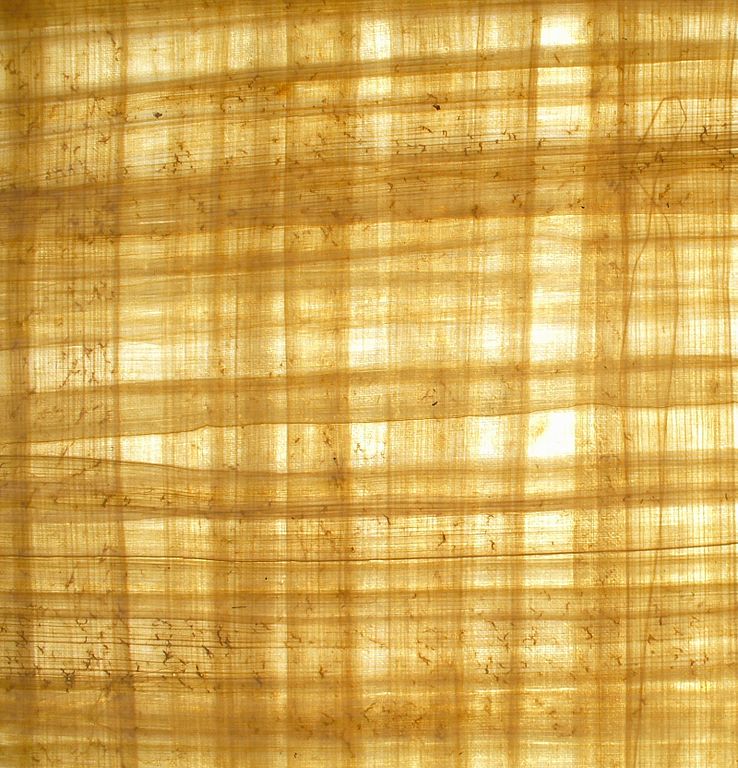

Centuries later the ancient Egyptians developed another technique, perhaps even more brilliant. They noted that the inner part of a particular marsh plant, the papyrus, was made of strips of a soft, smooth and durable substance. They joined strips together creating the first sheets. On this, it was possible to make drawings or graphic signs using vegetable and mineral inks.

Despite the long costly process and the shortage of product supply, the papyrus was still a big step forward. Less known is the fact that in South America the Maya had developed a similar process using a plant called Amate.

This technique had great luck: the Papyrus spread throughout the Mediterranean world and, nowadays, the name of that plant is found in the root of many terms referring to writing media (in English “paper”, “papier” in French, in German “papier”, in Russian “papiri”, in Spanish “papel”, etc... ).

This ancestor of paper has allowed the spread of the classical (Greek and Roman) thoughts, literature, philosophy, history and mathematics. Without the papyrus the works of Socrates, Pythagoras, Archimedes, Homer, Virgil and all the knowledge that is the basis of our modern civilization would not have been preserved. The ability to write and communicate has also been one of the bases of the greatness of Rome.Other techniques, such as parchment, which consisted of limed and scraped sheepskin, or metal tablets covered with wax used by the Romans were less fortunate due to their high costs.

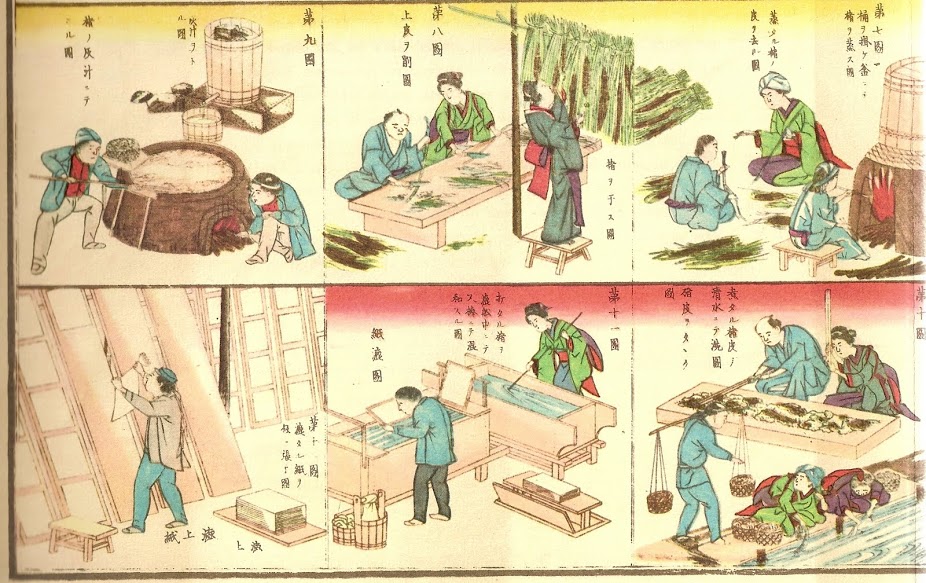

In China, in the year 105 AD, Ts'ai Lun, a member of the imperial court, made an important discovery.

Sitting on the edge of a stream, he watched a woman doing the laundry. As she rubbed the clothes against the rocks, some of the fibres broke off and floated a few yards downstream. He tried to touch this layer, but immediately the movement of water disunited the fibers; so he thought to lift the layer with a very narrow net and the fibers remained rigid. He then dried this layer in the sun which produced a smooth, soft, and durable sheet.

Why did this happen? Plants are composed of several elements: one of which is cellulose, made of soft, elastic and resistant fibers. Long cellulose fibers (cotton, flax, hemp, jute, etc.) are spun and woven to create fabric. Cellulose fibers too short to be spun can naturally felt, hooking up one another. To make paper, what was needed was to reduce the fabrics to a pulp using mortars, then lift them with nets.

Emperor Ho Ti was pleased with the invention that enabled them to produce sheets of paper in large quantities and with reduced costs compared to the Egyptian papyrus. The emperor praised Ts'ai Lun’s invention and covered him with honors. He wanted the technique to be taught to many Chinese artisans, but also wanted its secret to be kept and not transmitted outside China on pain of death. Neighboring countries attempted various imitations, some of which still survive today. In Thailand, they used the inner bark of the mulberry tree, made of pure cellulose. In Tibet they preferred a local shrub, the Lokta, while in Japan they used local seedlings.

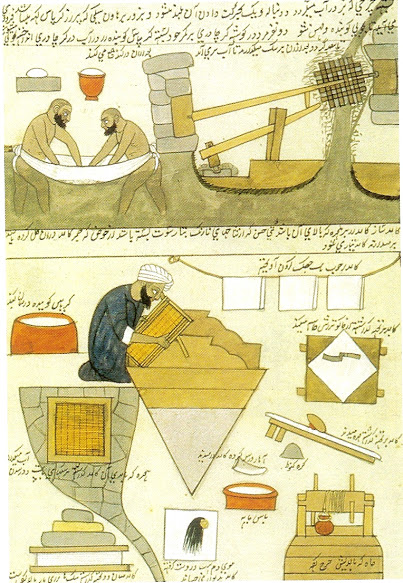

In 751 AD, during the Arab expansion after the death of Muhammad, Muslims conquered the Chinese cities of Central Asia. In one of these cities, Samarkand, they took some papermakers as prisioners. Astounded by their technique, the Muslims began to put it into practice and spread it throughout their territories, including Sicily and Spain, in addition to the Middle East and North Africa.

Five centuries later, around 1100, Italian merchants who traded with the Arabs, were able to learn the secrets of working the paper through Constantinople and brought them to Italy, Amalfi and Fabriano.

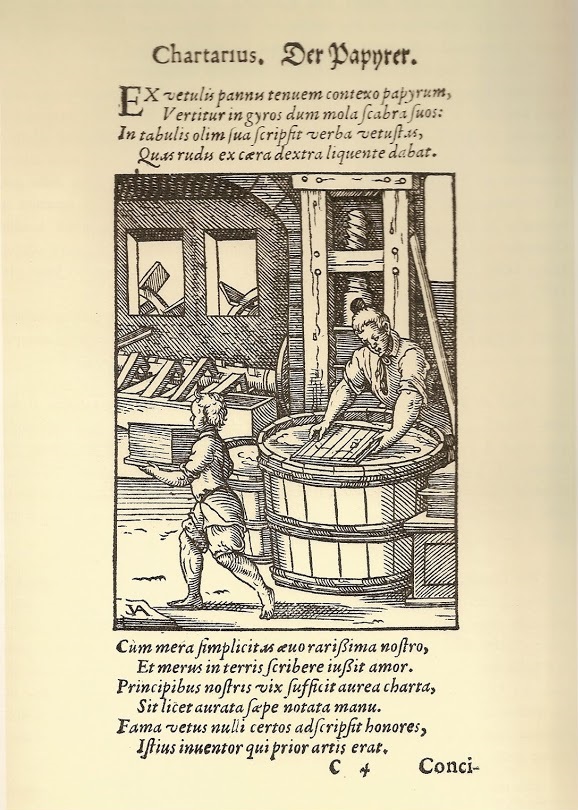

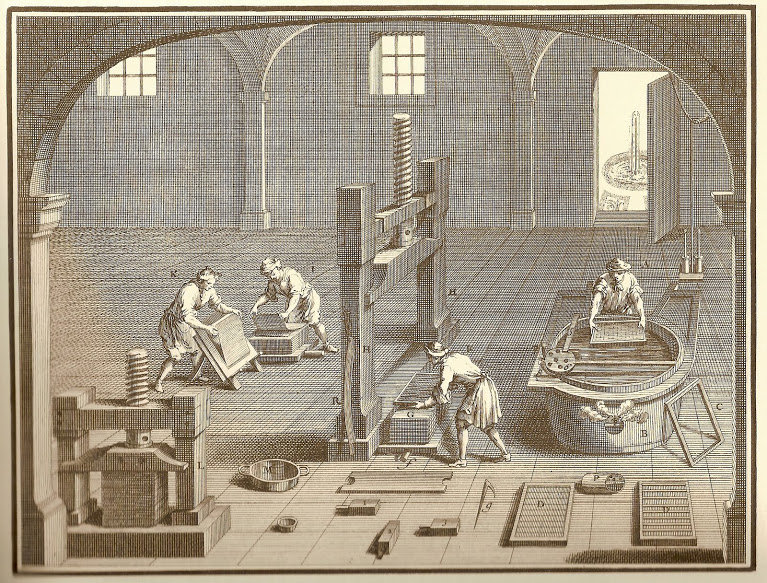

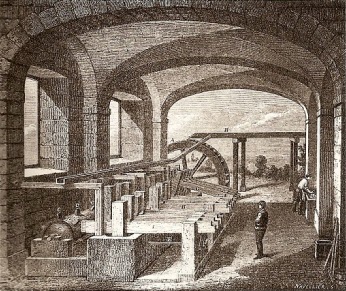

The technique in the centuries had changed. The fraying process of tissues was done with big spiked hammers activated by a mill’s wheel, rather than with the mortars used by the Chinese or the grindstone of the Arabs, this represented a great improvement. In order to speed up the drying process that, given the harsh climate of Europe, could not be achieved solely with the heat of the sun, a pressing stage was introduced. The product became better and better thanks to many other innovations.

One of these was the watermark, invented in Fabriano. A piece of metal was sewed in the net used to raise the layer of fibers: this way all the sheets produced were "marked", always in the same way and in the same position. Where the piece of metal is, there are fiber deposits and the paper remains thinner and more transparent. The watermark, born as a brand certifying the origin and quality of the paper, eventually became a decoration and a security seal, as you can appreciate nowadays on banknotes and other valued papers where it is used to prevent counterfeits. The people in Fabriano closely kept the secret of the technique of watermark and no paper artisan could leave the country without risking death.

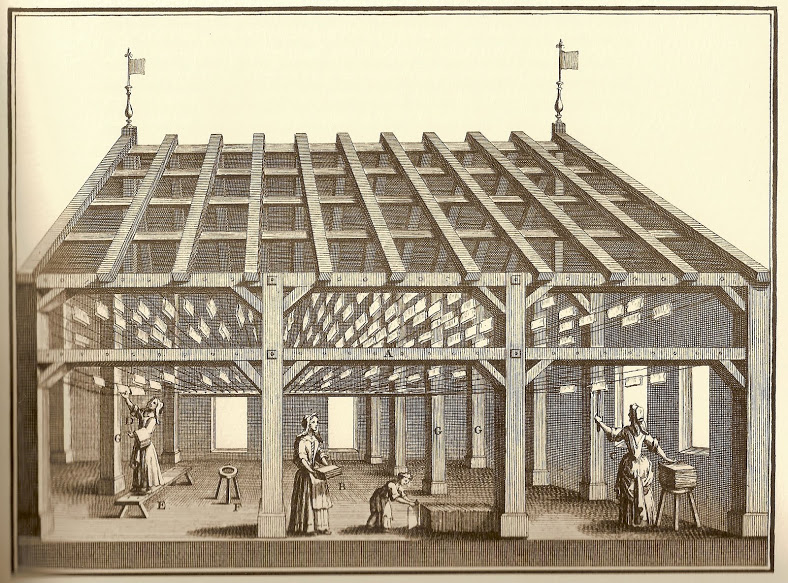

The Italian monopoly lasted several centuries, then in XV century paper factories spread across Europe, into Scandinavia and Russia, and across the ocean, only to North America. They were always built in proximity of waterways for two reasons: first, because 50 to 150 liters of water are necessary to obtain one kilogram of paper; second, because the only driving force able to activate the heavy fraying hammers was water. Often paper factories were also near harbors, where cotton and linen cloths, ropes of hemp and jute, and other necessary raw materials were more abundant.

The invention of paper in Europe contributed to the economic and cultural recovery after the dark centuries of the Middle Ages.Parchment was expensive and reserved only for the most important documents (1 sheep = 1 sheet) while papyrus is a sub-tropical plant. Paper, on the other hand, could be produced in large quantities and at relatively accessible cost. Everything that has been written, conceived, designed, calculated, all of the scientific inventions had been first spread through hand writing (and from the mid XV century printed) on handmade paper.

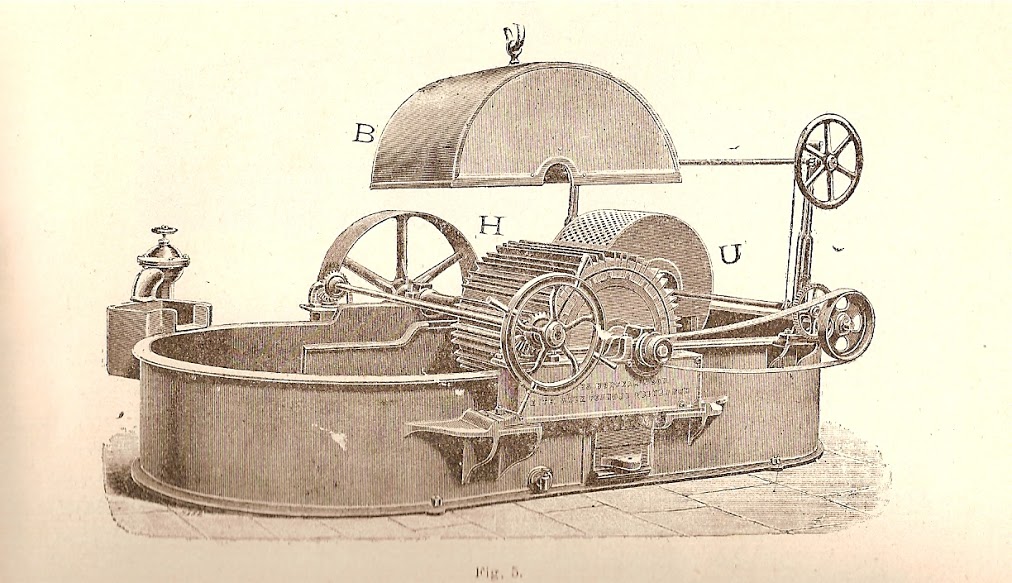

Thanks to handmade paper, the tragedies of Shakespeare, the verses of Petrarch, the works of Newton, the mathematics of Descartes, Galileo 's inventions, the designs of Durer, the declaration of human rights, the encyclopedia and even the first newspapers of the eighteenth century could spread and be shared.At the end of the XVII century the Dutch, whose land was full of mills, developed a new invention. Instead of the heavy and impractical hammers, they invented a machine that took their name: "Hollander" beater. This machine consists of an oblong tub partially divided in two by a septum. On one side a wheel with dozens of blades is mounted and below it, on the bottom of the tank, there are other cutting blades called "platen". Revolving the wheel has a scissor effect on the fibers suspended in the water. Water and fibers circulate in the refiner pushed by the movement of the wheel, and ground little by little at each passage. In the XVII century, a mill’s wheel produced the driving force for the grinding, as for the hammers. Nowadays, the mill has been replaced by an electric engine.

With this invention, the quality of the paper improved greatly. The new methods spread quickly throughout Europe, once again, despite the death penalty for those who revealed the improvement.

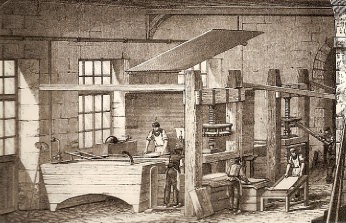

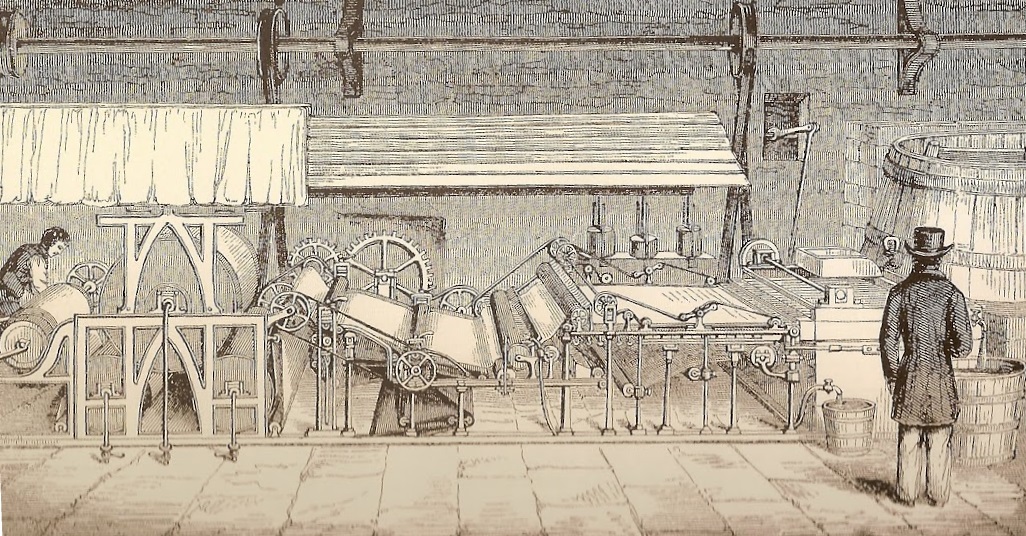

Our project in Peru has been indeed inspired by the Dutch technique with only marginal changes that developed afterwards. We use only cotton fibers, refined with the Dutch method: the sheets are formed one by one using nets with wooden frames and pressing them with vertical presses operated manually.In 1798 the first paper machine was built by L.N. Robert. This machine completely revolutionized the manufacturing system, since it produced a continuous strip of paper via a net covered drum rotating in a tank, where shredded plant fibers were suspended. In the next step, the continuous sheet passed between hot cylinders to be pressed and dried. The spread of these machines was slow -in Italy in 1850 only two of them existed - but inexorably replaced the traditional handmade paper due to the obviously lower costs.

Eventually, in 1800 the production was further increased when a chemical process was discovered, which allowed extraction of the cellulose directly from the trees’ wood.

Today paper is produced, all over the world, by huge continuous machines, hundreds of meters long and very fast. The most modern machine can create a 10 meter wide sheet at a speed of 2,000 meters per minute! But that's another story.

Today people say that paper, at least the one used for printing and writing, is a material in decline and surpassed. Perhaps in the future it will be partly replaced by electronic media. However, please bear in mind that the accumulation of scientific knowledge that led us to be able to write on our PC or to read texts on an e-book was made possible mainly by the invention of paper and the subsequent invention of printing with movable types. Without Ts'ai Lun’s invention we would spend hours pasting strips of papyrus or chasing sheep to be skinned in order to communicate and transmit our thoughts.